Locret: Enabling Long-Context Inference on Personal Devices

2024/09 Yuxiang Huang @Tsinghua & HKUST [中文][한국어][にほんご]

TL;DR: We introduce Locret, a lightweight training-based KV cache compression method that utilizes chunked prefill along with cache eviction. Locret achieves a $20\times$ and $8\times$ KV cache compression ratio compared to the full cache for Phi-3-mini-128K and Llama-3.1-8B-instruct, respectively, requiring less than 1 GPU hour of training. Locret is robust and compatible with multiple efficient inference methods. To our knowledge, Locret is the first framework capable of deploying Llama-3.1-8B or similar models on a single Nvidia 4090 GPU, enabling 128K long-context inference without sacrificing generation quality, and requiring minimal system optimization.

Background

Consumer-Grade Devices, End-Side LLMs, and Long-Context Inference

In recent years, we have witnessed a rapid expansion in the development of Large Language Models (LLMs). These models are demonstrating improved performance across nearly every domain, and developers are now focusing on creating more compact models specifically designed for consumer-grade devices.

Consumer-Grade Devices. To enhance the user experience with LLMs, hardware manufacturers are designing and producing cheaper, smaller GPUs, or integrating GPUs and NPUs into a single SoC to reduce the overall cost of AI models. For example, the Nvidia 4090, with only 24GB of GPU memory, can be installed in personal computers, and its price is controlled under $2000 USD. Companies like Apple and Qualcomm are also creating devices optimized for AI compute tasks, such as matrix multiplication and sparse operations. However, these devices still struggle with limited GPU memory and compute power.

End-Side LLMs. To overcome the challenges of memory and computational constraints, end-side LLMs are designed and trained to provide efficient AI services on the user’s device. These models typically have a compact size of less than 8B, often between 1B and 3B parameters. MiniCPM includes models ranging from 1.2B to 4B, Phi-3-mini is around 3B, and the Llama-3.2 series has 1B and 3B models. Despite their reduced size, these LLMs exhibit impressive capabilities, often rivaling 7B-8B models. To support more complex tasks like multi-hop reasoning, needle-in-a-haystack search, and AI-driven operating systems, these models are frequently designed to handle extended context lengths. MiniCPM-3-4B can process up to 32K tokens, and Phi-3-mini-128K and Llama-3.2-1B/3B even support 128K long-context inference, enabling end-side LLMs to perform long-context tasks effectively.

Long-Context Inference. Long-context LLM inference differs from traditional short-context inference in two key ways:

-

Increased computational overhead for attention mechanisms

As the context length increases, the computation required for attention scores grows quadratically, consuming a larger portion of the computational budget within each transformer block.

-

Higher memory requirements for key-value (KV) caching

Longer contexts necessitate larger KV caches, significantly increasing peak memory usage.

These challenges call for innovative techniques to reduce computational costs and manage memory more efficiently for long-context LLM inference. Consumer-grade devices, with their limited memory, cannot fully support such caches, making it crucial to develop KV cache compression algorithms for long-context inference on these devices to democratize LLMs.

Existing Efficient Inference Approaches

KV cache is often the bottleneck in inference throughput, leading to the development of several KV cache-centric efficient inference algorithms. We categorize them into algorithm optimizations and system optimizations.

Algorithm Optimization:

-

Quantization-based methods:

KV caches are stored in low-bit representations (e.g., 2-bits or 4-bits). Quantization can be applied either token-wise or by channel.

-

Sparsity-based methods:

No direct reduction of KV cache size is performed. Instead, attention matrix computation is optimized by identifying patterns in heads or layers, reducing the number of entries to be calculated.

-

Token-dropping:

- Eviction-based: A scoring function (usually manually designed) assesses the importance of each token (or cache unit), and units with lower scores are evicted.

- Token-merging (Attention Pool-based): Multiple adjacent cache units are merged into a single unit, such as in StreamingLLM, which uses an addition function to pool cache units.

System Optimizations:

-

Offloading-based:

The full cache is divided into chunks, and most of these chunks are offloaded to CPU or disk memory. Only the most relevant chunks are retrieved to the GPU during chunked prefill.

-

Hardware-aware algorithms:

Techniques like Flash-attention and Page-attention leverage modern GPU architectures to implement memory-efficient attention kernels, reducing peak GPU memory usage.

-

Designing better infrastructures:

More efficient programming languages and disaggregated inference frameworks can also improve the efficiency of long-context LLM inference.

A detailed comparison of the pros and cons of each approach for efficient long-context inference can be found in the Appendix.

Inference Spatial Complexity

From our perspective, existing inference techniques can be categorized based on their spatial complexity. Let $n$ denote the context length, and let $c\geq 1$ be a constant.

-

$O(n^2)$: Quadratic complexity, e.g., vanilla full KV cache inference. This complexity is extremely resource-intensive for all devices in long-context inference scenarios.

-

$O(c\times n)$: Linear complexity, e.g., full KV cache inference with chunked prefill. This complexity is still demanding in memory-constrained settings, as the KV cache size increases with context length.

-

$O(n/c)$: Linear complexity with constant reduction, e.g., quantization, sparse attention, and most system optimizations. While this complexity can reduce KV cache size significantly, it becomes impractical when context lengths extend to 128K or even 1M tokens.

-

$O(1)$: Constant complexity. This complexity can be achieved through token dropping or by using RNNs. Token dropping with a fixed cache size is $O(1)$, and RNNs like Mamba and RWKV also maintain constant complexity during inference.

To address the long-context inference challenge, we aim to design an algorithm with $O(1)$ complexity. Our goal is to develop a better scoring function to improve the accuracy of existing eviction-based algorithms. Instead of manually designing this function, we introduce a training paradigm to learn an accurate scoring function.

Locret

The overall framework of Locret is outlined below, where we first train the importance scoring function, followed by cache eviction and chunked prefill.

Training for Eviction

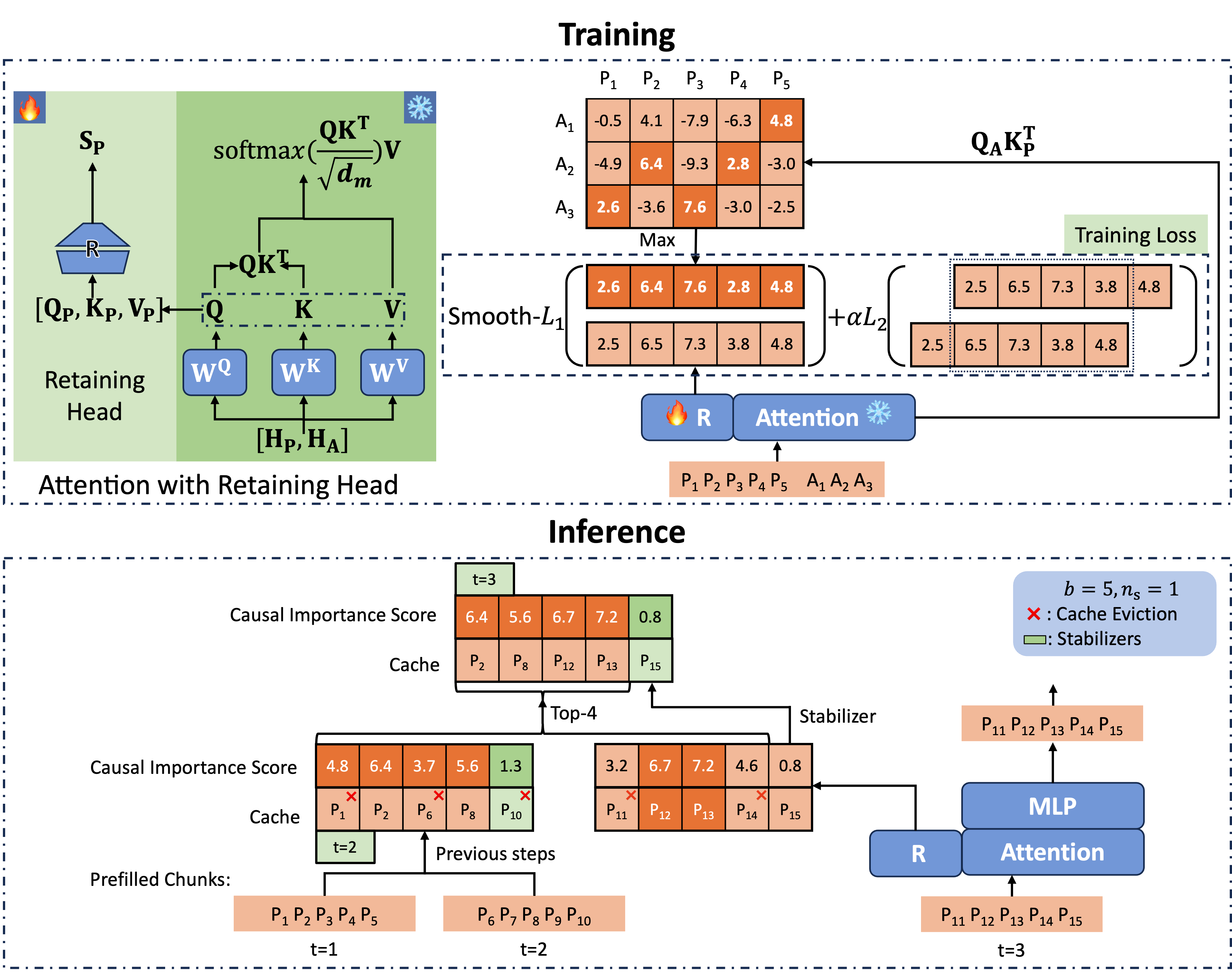

Retaining Head and Causal Importance Score

As depicted in Figure 2, we introduce an additional parameter called retaining head (denoted as $\mathbf{R}$) for each attention module. The retaining head is an FFN composed of two matrices and a non-linear activation function, defined as:

\[\mathbf{R}(\mathbf{x}) = \sigma(\mathbf{xW_1})\mathbf{W_2}.\]The input to the retaining head is the concatenation $[\mathbf{Q}, \mathbf{K}, \mathbf{V}]$, and it outputs the number of KV head values representing the importance, which we refer to as the causal importance score (CIS). The PyTorch-style code implementation is shown below:

cis = self.retaining_head_w2(

self.act(

self.retaining_head_w1(

torch.cat([h_q, h_k, h_v], dim=-1)

)

)

)

Formally, it is written as the following equation, where

$\mathbf{\tilde S}[k]_j^{(i)}$ is the CIS score of the $k$-th token at layer $i$ head $j$, i.e. cis[:, k, j] at layer $i$.

Training Objective

We generate the labels for CIS as follows. The retaining heads are trained on a small Question-Answer SFT dataset, where each entry consists of a single prompt and one answer. The CIS label for the $k$-th token at layer $i$ head $j$ is:

\[\mathbf{S}[k]_j^{(i)} := \max_{n_q(d) \leq p \leq n_q(d) + n_a(d)}\left(\mathbf{Q}_j^{(i)}\mathbf{K}_{j}^{(i)T}\right)_{p, k},\]where $n_q(d)$ and $n_a(d)$ represent the lengths of the prompt and answer in data $d$.

Note that the number of heads between Q and KV is not the same in GQA models, so we aggregate the maximum value among all the heads in the same KV group as the CIS label.

Let $L$ denote the number of layers and $h$ the number of heads. The training objective is:

\[\text{argmin}_{\mathbf{W_1}^{(i)}, \mathbf{W_2}^{(i)}, i=1, 2\cdots, L} \mathbb{E}_{d\in \mathcal{D}}\left[\sum_{i=1}^{L}\sum_{j=1}^{h}\sum_{k=1}^{n_q(d)}\mathcal{L}\left(\mathbf{\tilde S}[k]_j^{(i)}, \mathbf{S}[k]_j^{(i)} \right)\right]\]and the loss function $\mathcal{L}$ is:

\[\mathcal{L}\left(\mathbf{\tilde S}[k]_j^{(i)}, \mathbf{S}[k]_j^{(i)}\right) = \text{Smooth-}\mathcal{L}_1\left(\mathbf{\tilde S}[k]_j^{(i)}, \mathbf{S}[k]_j^{(i)}\right) + \alpha \mathcal{L}_2\left(\mathbf{\tilde S}[k]_j^{(i)}, \mathbf{\tilde S}[k-1]_j^{(i)}\right),\]where Smooth-$\mathcal{L}_1$ is the smooth 1-norm and $\mathcal{L}_2$ is the 2-norm.

Following this approach, we train the retaining heads on LongAlpaca for 3000 steps. The training time is less than 1 GPU hour.

Inference with Retaining Heads

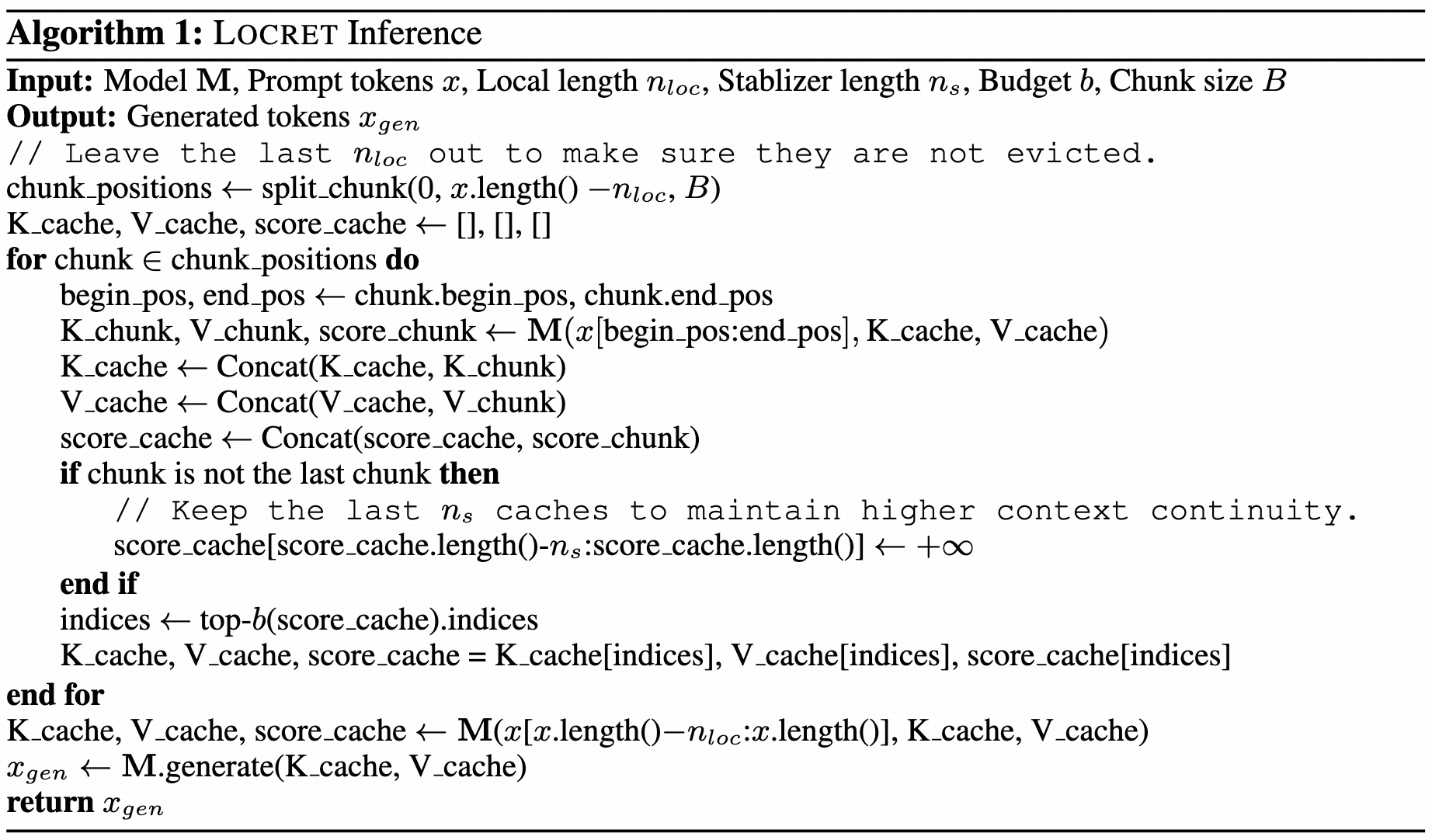

We now have an accurate scoring function capable of predicting the CIS. We use chunked prefill and perform cache eviction based on the predicted CIS.

As shown in Figure 2, we leave the last $n_s$ cache units at every head and layer, called stabilizers, to enhance performance. We maintain a cache set with a static budget size $b$ and apply chunked prefill. When processing the next chunk, we first calculate the CIS, assign $+\infty$ to the stabilizers, then concatenate the current chunk’s cache with the cache set. Finally, we retain the cache units with the highest $b-n_s$ CIS scores. This method keeps the spatial complexity constant, as the cache set has a fixed size. The retaining heads allow accurate scoring and retain the most critical cache units for subsequent operations. The pseudocode for Locret Inference is shown in Algorithm 1.

Benchmark: Budget-Constrained Long-Context Inference

Performance Benchmark

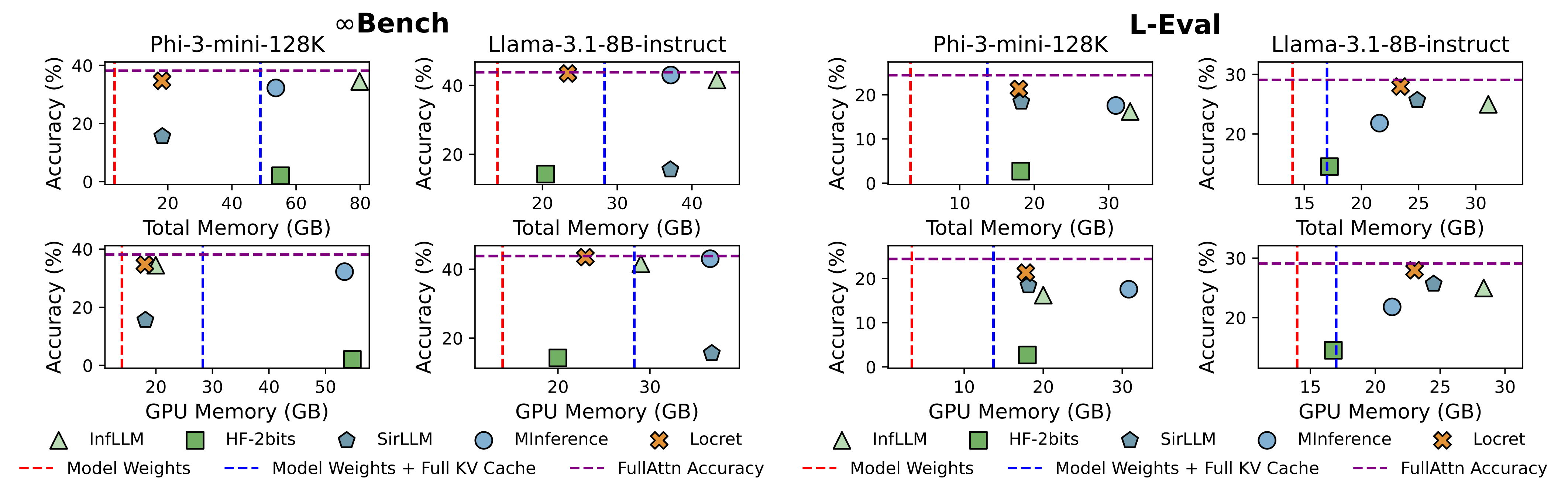

We selected 5 baseline methods, which correspond to existing approaches, and compared them with Locret on Phi-3-mini-128K and Llama-3.1-8B-instruct. The budget size for Locret was set to 6000 and 16384, respectively. The baselines are described below:

| Method | FullAttn | InfLLM | HF-2bits | SirLLM | MInference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Vanilla full KV Cache | System: Offloading | Algorithm: Quantization | Algorithm: Token Dropping-Eviction | Algorithm: Sparsification |

The results are displayed in Figure 1. Locret achieved the highest benchmark score while using relatively low memory. Methods with lower memory usage than Locret completely failed in some or all settings.

Speed Benchmark

We also evaluated the inference speed of Locret. We compared our method with all baselines on a single Nvidia 4090, which has only 24GB of GPU memory. The results are as follows. Note that some methods could not operate in such a constrained environment, so we truncated the input context until the corresponding method could run without causing an OOM error.

| Model | Metrics | FullAttn | InfLLM | HF-2bits | SirLLM | MInference | Locret | HF-2bits* | MInference* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phi-3-mini-128K | tok/s | - | 2276.38 | - | 2352.20 | - | 5080.85 | 1098.51 | 4099.92 |

| Phi-3-mini-128K | Context Length | 128K | 128K | 128K | 128K | 128K | 128K | 30K | 14K |

| Phi-3-mini-128K | Accuracy | OOM | 99.83 | OOM | 1.69 | OOM | 100.00 | 0.00 | 13.56 |

| Llama-3.1-8B-instruct | tok/s | - | 2287.66 | 1365.51 | 1589.75 | - | 3209.10 | 3680.06 | 5135.74 |

| Llama-3.1-8B-instruct | Context Length | 128K | 128K | 128K | 128K | 128K | 128K | 30K | 25K |

| Llama-3.1-8B-instruct | Accuracy | OOM | 100.00 | 35.59 | 1.69 | OOM | 100.00 | 26.78 | 20.34 |

Orthogonality to Quantization and Token Merging

Previous research has shown that eviction-based methods like H2O struggle when combined with KV cache quantization. However, Locret is robust even when quantization is applied.

| Setting | M | M-4bits | $-\Delta$ |

|---|---|---|---|

| M=FullAttn | 29.08 | 28.52 | 0.56 |

| M=Locret | 27.96 | 27.11 | 0.85 |

The performance drop due to quantization on Locret is only slightly greater than that observed with the full attention method, indicating that Locret is a quantization-friendly approach.

Additionally, we can maintain an attention pool with a static size to store evicted cache units. LoCoCo achieves this by applying convolution to the non-heavy-hitters identified by H2O. By replacing H2O with Locret, we obtain a combination of both methods.

| Method | LoCoCo | Locret | Combination |

|---|---|---|---|

| L-Eval | 26.01 | 27.96 | 28.70 |

Locret achieved a higher score than LoCoCo, and the combined algorithm outperformed both standalone methods. This suggests that Locret provides a more accurate scoring function than H2O, and the two methods complement each other, demonstrating their orthogonality.

Acknowlegement

We gratefully acknowledge the following individuals for their contributions. Without their support, this project would not have been possible.

- Binhang Yuan (Professor @HKUST), advisor of this project during Yuxiang’s internship at HKUST.

- Xu Han (Research Professor @Tsinghua) and Zhiyuan Liu (Professor @Tsinghua), advisors from the THUNLP lab, who provided invaluable assistance and insightful feedback.

- Chaojun Xiao (PhD Student @Tsinghua), author of InfLLM, who offered valuable advice and proofread the paper.

- Ruisi Cai (PhD Student @UT Austin), author of LoCoCo, who helped with training LoCoCo and provided suggestions for extending it to the Llama-3.1 series.

- Xinrong Zhang (PhD Student @Tsinghua), author of InfiniteBench, who offered insights into the original design of the InfiniteBench benchmark.

- Weilin Zhao, Chenyang Song, Shuo Wang, and Yuan Yao for their valuable discussions.

Citation

Please refer to our ArXiV paper.

@article{huang2024locret,

title={Locret: Accelerating Long-Context LLM Inference with Retaining Heads},

author={Yuxiang Huang, Binhang Yuan, Xu Han, Chaojun Xiao, Zhiyuan Liu},

journal={arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.01805},

year={2024}

}

Appendix

| Category | Type | Pros | Cons | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Algorithm | Quantization | Minimal performance loss with >4-bit quantization. Easy to implement. | Significant performance loss at 2-bits. Slow inference. Requires specialized hardware. Constant KV cache size reduction. | KIVI, KVQuant |

| Algorithm | Sparsification | Very fast inference speed. Low runtime GPU memory for internal variables. | No reduction in KV cache size. Noticeable performance drop in denser models (e.g., MLA, GQA). | MInference, FastGen |

| Algorithm | Token Dropping - Eviction | Fast inference speed and simple implementation. Bounded memory usage. | Significant performance degradation due to inaccurate scoring functions. | H2O, SirLLM |

| Algorithm | Token Dropping - Merging | Bounded memory usage. | Some algorithms require additional training. Severe performance loss if post-training is insufficient. | StreamingLLM, LoCoCo |

| System | Offloading | Almost no performance degradation. | Very slow inference due to limited I/O bandwidth. Requires careful offloading optimization. | InfLLM, FlexGen |

| System | Hardware-Aware Algorithms | High hardware utility, fast inference speed, no accuracy loss. | No reduction in KV cache size. Needs adaptation for specific hardware architectures. | Flash-Attention, Page-Attention |

| System | Better Infrastructures | Suitable for enterprise-level applications. | Extremely difficult to develop. Limited applicability across different scenarios. | KTransformers, HexGen |